Deducible UI January 27, 2012

A Brief History

I like automating things. I don’t like having to reiterate myself: my dream is to always be able

to add only the necessary amount of information in order to make something possible.

This is one reason, for instance, why I hate expressions like

ArrayList<String> x = new ArrayList<String>();… it always makes me feel like I’m talking to a

retard (compiler).

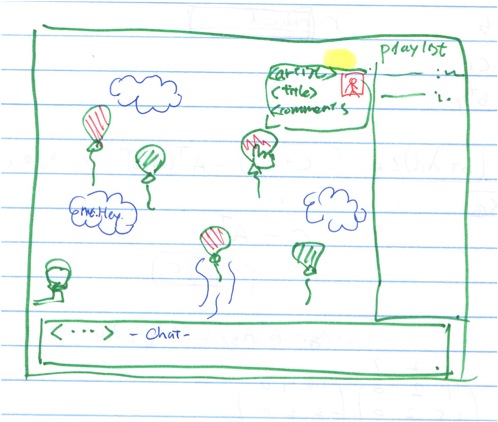

In 2006/7, I wrote some demos for RPyC to show how easy network-related

tasks become. I chose something rather complex, a chat client, to show that all the code sums

up to a few lines: clients invoke a method on the server, say broadcast(str), and the server

then invokes callbacks on all of its clients, sending them the message.

In order to make it usable, I had to write a GUI: I chose Tk, because it comes with python and is quite simple; I knew there were better toolkits, but my GUI was meant to be basic enough to be doable in any toolkit. It occurred to me, then, that I wrote ~20 lines show-casing RPyC and ~100 lines of horrible GUI code, and that something must be really wrong here. And by here I mean everywhere.

Note: throughout the article, I’m using the word GUI to mean any interactive user interface, be it graphical (Qt, GTK, wxWidgets, …) or terminal-based (

cursesand the like). Basically, anything that doesn’t block on a single line of input, like shells.

GUI Designers

So you might say, “Dude, just use QtDesigner or something”. A GUI designer lets you visually place components and makes your life much easier – drag and drop your widgets and double-click on a button to write its action. Very easy indeed. But I would like to offer a different angle on the subject: just like the invention of the teacup has hindered the technological advance of China, so do GUI designers hinder us from developing better GUIs. These designers offer a local optimum which we fail to surpass, and this leaves us with the mediocre UIs and development tools we have today. And get me going about XAML.

Think about it: you have to design a GUI. So yeah, it’s kind of simple, but doesn’t that break DRY? You have the code and you have the GUI – two faces of the same idea. Obviously, one should be derived from the other.

For the lion’s share of programs, the UI is highly deterministic – there’s some information that needs to be displayed to- or gotten from the user, and the bindings is trivial. Consider a login screen: you want to get a username and a password, use them somehow, and proceed to the next screen. This is a repeating task, and I’d guess that for ~80% of the programs in the world, it’s easy enough to automatically deduce how the UI should look, given the task at hand. And I’m not talking about machine learning algorithms or designing “families of tasks” – way simpler than that! Just define a mapping between programmatic primitives and their visual representation.

Deducing UI

The ultimate goal is to take “pure code”, unaware of UI, and by adding the necessary metadata, be able to automatically create (“deduce”) a GUI for it. In fact, I’d like to expose programmatic APIs to a human – completely interchangable programmatic- and human- interfaces. Think how cool it could be to import Adobe Photoshop and run a directory full of pictures through its filters, instead of doing so through the UI… without Adobe having to write a separate GUI and programming toolkit.

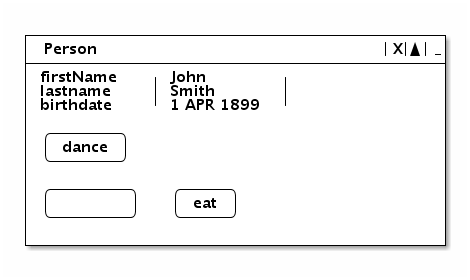

The UI needn’t be an eye-candy, at least at the beginning; it just has to be good-enough. It won’t work for games or complex applications like Office, but for it would be just fine for a chat client. Let’s assume the following mapping:

- An object is represented by a window

- Read-only instance attributes are represented as labels

- Writable instance attributes are represented as textboxes

- Methods are represented by buttons. If a method requires arguments, it would be preceded by textboxes

Of course we could change textboxes and labels to reflect the attribute’s or argument’s type –

DateTime would be represented by a DatePicker, int could be represented by a number box with

up/down arrows, etc. And of course the framework is free to change the mapping however it wants,

to achieve better, more coherent representation. The mapping above is just a rough draft.

Now, instances of a class like the following:

class Person {

public String firstName;

public String lastName;

public DateTime birthdate;

public void dance() {...}

public void eat(String foodstuff) {...}

}would turn into

with just a little bit of binding in the form of:

class Main {

static public void Main(String[] args) {

Person p = new Person(...);

guify(p);

}

}Straightforward, isn’t it? You can already begin to see the benefits. This framework would obviously require some sort of decoration (annotations in Java, attributes in C#, …) on which classes and which class members are to be exposed, and perhaps some extra metadata, like a picture to show instead of a method’s name, or some layout information – but it’s perfectly doable. And we can turn it better looking (unlike my beautiful ASCII art example), by using better UI primitives and a better mapping between objects and their representation; but let’s leave it for now.

I wrote a a simple prototype of this and lo and behold, it actually worked! But when you try to

use it in a real-life applications, the going gets tough: things are updated behind the scenes

(not through our UI framework) and we need to reflect these changes in the UI. For instance,

an element is added to a list via the list’s add() method - how can the GUI become aware of that?

Well, we can use observable objects, which the GUI

would observe; so instead of using an ArrayList<T>, you’d simply use an ObservableArrayList<T>.

But creating an observable counterpart for every class is a considerable effort on the framework’s side, and it breaks software modularity: the framework has to be aware of every 3rd party class that you wish to expose, or at least allow you to provide the means to expose them. Another downside of this scheme is that your code becomes aware of the GUI: if we’ve so far managed to keep our code clean of GUI primitives (we only required some metadata), all of the sudden you must replace your lists with GUI-observable-lists. Bummer.

Another issue is that using synchronous programming techniques (blocking operations) does not play well with this model: when does the GUI gets its “runtime”? How can we keep it from freezing? Who’s providing the entry-point of the program? Does it run in a separate thread? If so, we risk polluting our code with GUI-related locks (which is countering the whole purpose); and besides, threads suck and add the incurred complexity is never worth it. The only feasible option is asynchronous programming (via a reactor) – but requires that your code be programmed this way, and it’s quite nasty to write such code without proper language support (e.g., lack of closures, coroutines, etc.).

“No Way”

As I said, I’ve been toying with this idea from 2006, and I always get the same response from colleague programmers: “it would never work”, “it won’t be good enough”, “no one would want to use it”, “users need their eye-candy”, “I need tight control over the layout”, and what not. Skeptics galore. My answer is always the same: you never know what your user wants – so who are you to decide? And besides, you’re always to lazy to support proper customization of UI, so your user must live with your decisions.

Sure, there are books and dissertations about UX, and you’ve read them all; but why not just provide good-enough defaults, and let the rest be customized by the user? Let the framework deduce a sane layout for your code – but let’s make everything movable/resizable/dockable. This way, if it makes more sense to place button X to the left of button Y, the user can do so himself. And let’s remember the user’s preferences in a file, which we’ll load each time the application runs. And by “user” I’m also talking about your UX expert – let him/her decide on a default look (i.e., the preferences file) for the application, which will be shipped with your product, but the end-user would still be able to move things around. Wouldn’t it be easier? And if you insist, here’s the place to stick some machine-learning magic, in order to deduce better UIs by default.

So anyhow, I had a working proof-of-concept somewhere, but I think I lost it. It wouldn’t be too hard to recreate it, but at the moment I’m more concerned with UI combinators, which I’ll cover in a future post. Fully deducing a UI is quite a challenge, as a detailed above, but it’s doable nonetheless, and the added-value is huge! I’ll get back to it some day, perhaps after I have better UI combinators… but in the meantime, is there anyone in the audience who’s willing to pick it up?