Wizard Dialog Toolkit February 11, 2012

Following my Deducible UI post, and following some of the criticism it had received, I’d like to share something I’ve been working on (read: experimenting with) at my work place. You see, we have some “interactive wizards” that storage admins use to connect storage arrays to their hosts (say, a DB server). These wizards prompt you with questions like your what’s your username, the name of the pool/volume, whether it’s an iSCSI or a Fiber Channel connection, etc., and then they go and perform what you’ve asked for.

These wizards operate in a terminal environment, but we’ve had thoughts to make GUI/web versions of them. This would be a considerable effort with the current design. Another issue they currently have is the mixing of “business logic” and presentation together. For instance, the code that scans the devices attached to your host also prints ANSI-colored messages or reports its progress. All in all it works fine, but there’s lots of room for improvement.

I began to investigate this corner a month or two ago. The initial observation was that such wizards have a pretty rigid and repetitive structure, thus we can find some abstraction or a “toolkit” for “expressing” wizards more compactly. This has also led to the realization that once the business logic and presentation are separate, there’s no reason to limit ourselves to terminal-based interaction: our wizard-toolkit could do the plumbing and work with terminals, ncurses, GUIs, web-browsers, etc. The business logic would remain oblivious, and we could have a nice GUI at zero-cost!

There was also a second issue of styling, i.e., printing text in color, that I wanted to get r

id of. This part was easy: I thought, why not employ the model of HTML and CSS? Let’s separate the

structure (semantics) of the text from its styling. Instead of printing a banner for titles,

we’ll display a Title object, whose exact appearance is determined by a “style sheet” (a class,

of course, not actually a text document).

For instance, when we’re using a color-enabled terminal, the title would be printed in bold and

followed by an empty line; but if our terminal is color-blind, we’ll render the text centered and

surrounded by = marks. Another example is error-handling: instead of printing error message

in red every time, we’ll display an Error object; on a terminal, this would be rendered as

red text, but when running in a GUI, rendering this object would pop up a message box.

I’m going to ignore this for the rest of this post, as this is really a side issue.

Now let’s get to expressing wizards, or more generally, dialogs. Following some earlier iterations,

I came to the model where a dialog is a “container object” that’s made of dialog elements. These

elements can be output-only (such as a welcome message), or input-output (such as a message

telling you to choose one of the available options). A dialog is “executed” by a DialogRunner that

renders it and returns the results gotten from the user. It’s quite important to note that dialog

elements within a single dialog cannot be interdependent – that is, if you want to ask the user

for his name and then show "Hi there %s" with the user’s name, this has to be done as two,

serial dialogs.

That was quite a lot of babble – let’s see this in action:

class MyApp(WizardApp):

def main(self):

iscsi = Option("iSCSI")

fc = Option("FC")

d = Dialog(

Text(Title("hello world")),

Input("un", "Username"),

Password("pw", "Password"),

Choice("conf", "What do you want to configure?", [iscsi, fc]),

)

res = self.ui.run(d)

if res["conf"] == fc:

self.config_fc(res)

else:

self.config_iscsi(res)

...

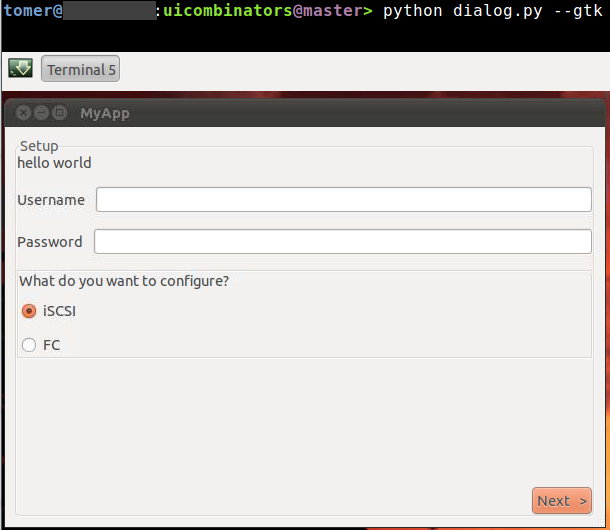

if len(sys.argv) == 2 and sys.argv[1] == "--gtk":

MyApp.run(GtkDialogRunner("My App"))

else:

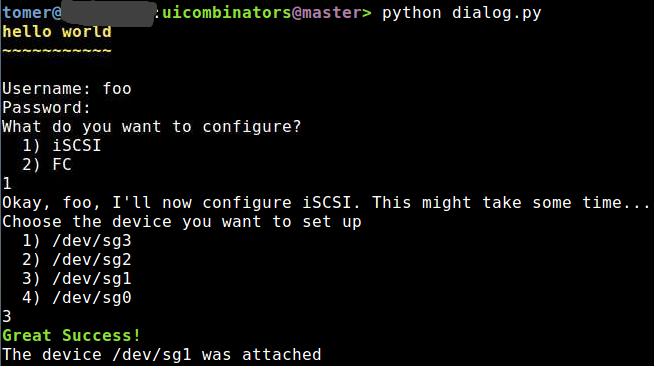

MyApp.run(TerminalDialogRunner(ANSIRenderer))It’s a short and incomplete snippet of course, as I’m only going to cover the big picture. The

main function creates a dialog object d and passes it to ui.run, which “runs” the dialog

and returns the results, as a dictionary. Notice that the dialog elements Input, Password

and Choice all take a first parameter – this is the key under which the result would be placed

in the returned dictionary, e.g., res["un"] would hold the user-provided user name, and

res["pw"] would hold the password. Text, on the other hand, is an output-only element,

so it doesn’t return anything and doesn’t take a key. Long story short, we’re asking the user

to enter some information and choose one of two options, and then continue processing based on the

selected option. At the bottom, we determine how to run the application based on a command-line

switch: if --gtk is given, we’ll run the dialogs through the GtkDialogRunner; otherwise,

we’ll use the TerminalDialogRunner.

And how does it look like? When running on a terminal:

And with a single command-line switch, we run as a GTK application:

So of course it’s far from perfect, but then again, it’s a small research project I’ve only put ~15 hours into. It suffers from some of the problems I’ve listed in the deducible UI post, for instance, the GUI hangs when the business logic performs blocking tasks. This could be solved by moving to a reactor-based model, but I’ve tried to keep the existing wizard code in tact as much as possible. A hanging GUI is not nice, but it’s not the end of the world either, and there are numerous ways to overcome this.

Another benefit this design brings along is the ability to automate testing by using mock dialog

runners. Since our business logic is only exposed to the returned dictionary, we can use a

dialog runner that actually displays nothing and returns a scripted scenario each time. We can even

go further: because our business logic “talks” in high-level primitives like Choice, we can compute

the Cartesian product of all choices and run through each of them. We can show that we’ve covered

all paths! And we can do this automatically… without people hitting buttons and keeping logs of

their progress.

Anyway, I just wanted to show that it’s feasible. I’m not releasing any code as this project is currently in very early stages, and it’s something I do at work. Perhaps we’ll open-source it in the future, if it proves useful enough.